Identification of Invasive and

Reemerging Pests on Hazelnuts

V.M. Walton, U. Chambers, A. Dreves, D.J. Bruck, and J. Olsen

Hazelnuts are produced in many countries, including the United

States. Hazelnuts are grown on approximately 30,000 acres in the

Willamette Valley, accounting for about 99 percent of U.S. production

and 5 percent of world production. Turkey produces more than

70 percent of total world hazelnut production.

Hazelnut species that occur naturally in the Willamette Valley

include the wild native hazelnut, which is found in uncultivated

woodland areas as well as in some parks. Wild and cultivated hazelnuts

are attacked by similar pests.

This publication is intended to increase producer awareness of

important pests that occur in hazelnut orchards in the Pacific Northwest.

The biggest threat to hazelnut production since the 1970s has

been Eastern filbert blight. This disease is found in two-thirds of the

Willamette Valley and, if not controlled, can kill mature trees.

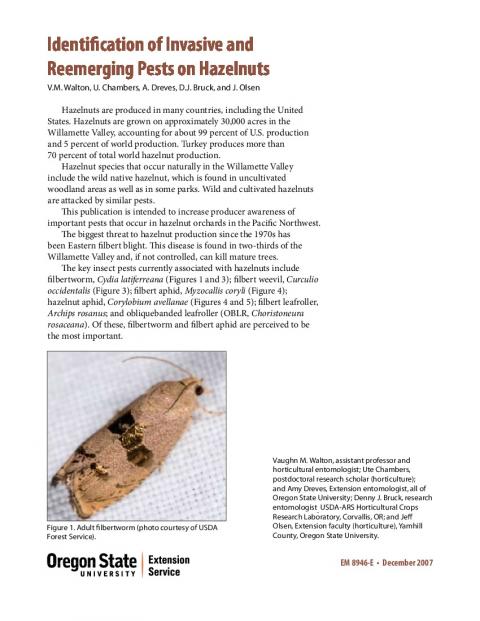

The key insect pests currently associated with hazelnuts include

filbertworm, Cydia latiferreana (Figures 1 and 3); filbert weevil, Curculio

occidentalis (Figure 3); filbert aphid, Myzocallis coryli (Figure 4);

hazelnut aphid, Corylobium avellanae (Figures 4 and 5); filbert leafroller,

Archips rosanus; and obliquebanded leafroller (OBLR, Choristoneura

rosaceana). Of these, filbertworm and filbert aphid are perceived to be

the most important.

EM 8946-E • December 2007

Vaughn M. Walton, assistant professor and

horticultural entomologist; Ute Chambers,

postdoctoral research scholar (horticulture);

and Amy Dreves, Extension entomologist, all of

Oregon State University; Denny J. Bruck, research

entomologist,, USDA-ARS Horticultural Crops

Research Laboratory, Corvallis, OR; and Jeff

Olsen, Extension faculty (horticulture), Yamhill

County, Oregon State University.

Figure 1. Adult filbertworm (photo courtesy of USDA

Forest Service).

2

Filbertworm and filbert weevil

Filbertworm and filbert weevil larvae

feed on nut kernels and can cause between

20 and 50 percent damage if untreated.

Both species cause similar damage

(Figure 2). Infested nuts have holes in the

shell, and the kernels are damaged by feed-

ing and contaminated with feces.

Filbertworm and filbert weevil popula-

tions also infest several oak species and

wild hazelnut stands. These populations

can migrate to nearby hazelnut orchards

and cause crop loss.

Identification

Filbertworm larvae are creamy to pink

and approximately ½ inch long (Figure 3).

They have three pairs of true legs and addi-

tional pairs of prolegs toward the posterior

portion of the body. After emerging from

nuts, larvae defend themselves by regur-

gitating a red excretion and moving rela-

tively fast.

Filbert weevil larvae are similar in

length, but are grublike and creamy col-

ored (Figure 3). Larvae are rather inactive

when touched and curl in a c-shape. They

have only three pairs of true legs.

Life cycle

The majority of adult filbertworm

moths (Figure 1) emerge from late June

to early October. They lay eggs near nut

clusters and on leaves close to developing

husks. After hatching, the minute larvae

search for a nut and feed on the part of

the husk that adheres to the nut until they

locate a soft spot through which they can

enter the nut. They may feed in the nut for

several months before reaching maturity.

The mature larvae exit the nut by chew-

ing through the side of the shell or enlarg-

ing the entrance hole. They drop to the soil

beneath the tree and overwinter in organic

material and soil to a depth of 2 inches.

Damage may occur as early as late May,

when nut development begins. Damaged

nuts often drop early.

Figure 3. Filbert weevil larvae (left and right) are more grub-

shaped and creamy colored than filbertworm (center), which has

three pairs of true legs, prolegs, and a darker body color.

Figure 2. Hazelnuts with clearly visible emergence holes made by

filbertworm or filbert weevil.

�

Little has been learned about the biology of the filbert weevil since

initial work was done by Dohanian in 1944. Adult weevils cut small

holes in the nut shell and lay eggs in the nut during the early part of the

season (May to June). Larvae hatch and feed on the kernel until they

reach maturity in August. Damage is not observed until the end of the

growing season.

After nuts drop, larvae exit and burrow into the soil to a depth of

3 to 6 inches. Adults emerge in the spring after hibernating as larvae in

the soil for up to 3 years.

Pest status

Studies by Dohanian indicated that roughly 50 percent of infested

nuts are damaged by filbert weevil and 50 percent by filbertworm.

Infested hazelnuts collected in cultivated and abandoned orchards in

2006, however, showed 91 percent filbertworm and 9 percent filbert

weevil. Collections of nuts in several orchards during 2007 did not reveal

filbert weevil infestations.

Filbert aphid and hazelnut aphid

Filbert aphid and hazelnut aphid feed on husks and leaves. Aphid

feeding drains nutrients from leaves and may reduce photosynthesis

due to the growth of black sooty mold on the aphid’s honeydew excre-

tions. It is believed that reduced photosynthesis may result in substantial

crop losses in the long term. It is unknown whether large populations

of aphids feeding on husks can cause premature nut drop and lower nut

quality.

Identification

Often both species are found on a leaf, which makes it easier to dis-

tinguish them (Figure 4).

Filbert aphid has smaller cornicles, which often are not visible to the

naked eye. Cornicles look like tail pipes and are used to excrete honey-

dew. The antennae and legs are the same color as the body.

The hazelnut aphid, on the other hand, is often difficult to see, as it

is greenish and blends in with plant tissue. The cornicles of this species

are longer and more visible. The antennae and legs are darker than the

body.

Pest status

Before the mid-1980s, the filbert aphid was considered the only

important aphid pest of hazelnuts in Oregon. Aphids were controlled

with several sprays of organophosphates each season.

The management of filbert aphid changed after the introduction of

a cool-climate French strain of the braconid parasitoid Trioxys pallidus

between 1984 and 1986. This parasitoid wasp spread rapidly and became

established as a consistent control agent.

Figure 4. Hazelnut aphid (top)

and filbert aphid (bottom).

Cornicle

Cornicle

4

The hazelnut aphid, a newly invasive

species, was first reported by the Oregon

Invasive Species Council in October 2003

on hazelnut trees in the northern Wil-

lamette Valley. Recent collections of this

aphid from various orchards and wild

habitats show that this pest has spread

rapidly into many hazelnut production

areas. However, little is known about the

status of this aphid in hazelnut orchards.

Several management changes have

taken place since the initial release of

T. pallidus. Large aphid populations

on husks have been reported recently,

leading to increased chemical control

efforts by growers. Little is known about

the underlying reasons for increased

aphid activity in hazelnut orchards in the

Pacific Northwest. Sampling was conducted in several orchards in the

Willamette Valley during 2007, and large populations of both species

of aphids were found on leaves. Husks were primarily populated by

hazelnut aphid (Figure 5).

In addition, there have been several reports of poor biological

control. Our data suggest that hazelnut aphid populations on husks

showed low parasitism rates. Collections of mixed aphid species from

different field sites during 2007 indicate parasitism of 15 percent

(n=15,819) on leaves and 2.84 percent (n=3404) on husks. Other

research has found parasitism rates between 11 and 28 percent, resulting

in aphid population reductions of 26 to 48 percent.

Conclusions

Hazelnut producers are continuously confronted with changes in the

insect pest and disease complex. In order to continue the production of

superior quality hazelnuts and remain profitable, producers need to be

aware of the specific pest complex in their production units.

Initial survey work in hazelnut orchards indicates that the focus

should be on monitoring and on alternative and integrated pest control.

“Forgotten pests” such as filbert weevil and hazelnut aphid may be

important. Producers need to be aware of these pests and be willing to

use newly available, environmentally safe control methods. Examples

of such options include entomopathogenic nematodes (nematodes that

prey on insects), mating disruption, and organic compounds. Further

work needs to be done on the biology and ecology of filbert weevil and

hazelnut aphid.

The newly invasive hazelnut aphid may change the current aphid

management protocol in hazelnut orchards. Future work on aphids may

include the preservation of natural enemies of filbert aphid and the

importation of new natural enemies for hazelnut aphid.

Figure 5. Hazelnut aphid feeding on husks and parasitized aphid

mummy (bottom right).

hazelnut aphid

�

For more information

OSU Extension Service

Olsen, J. 2002. Growing Hazelnuts in the Pacific Northwest. Oregon

State University Extension Service, EC 1219. Revised July 2002.

Many OSU Extension Service publications may be viewed or

downloaded from the Web. Visit the online Publications and Videos

catalog at http://extension.oregonstate.edu/catalog/

Copies of our publications and videos also are available from

OSU Extension and Experiment Station Communications. For prices

and ordering information, visit our online catalog or contact us by

fax (541-737-0817), e-mail (puborders@oregonstate.edu), or phone

(541-737-2513).

Other publications

AliNiazee, M.T. 1998. Ecology and management of hazelnut pest

management. Ann. Rev. Entomol. 43:395–419.

Bruck, D.J. and V.M. Walton. 2007. Susceptibility of the filbertworm

(Cydia latiferreana, Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) and filbert

weevil (Curculio occidentalis, Coleoptera: Curculionidae) to

entomopathogenic nematodes. J. Inv. Path. 96:93–96.

Dohanian, S.M. 1944. Control of filbertworm and filbert weevil by

orchard sanitation. J. Econ. Entomol. 37:764–766.

Dunning, C.E., T.D. Paine, and R.A. Redak. 2002. Insect–oak

interactions with coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) and Engelmann

oak (Q. engelmannii) at the acorn and seedling stage. USDA Forest

Service Gen. Tech. Rep. PSW-GTR-184.

El-Haidari, H. 1959. The biology of the filbert aphid, Myzocallis coryli

(Goetze) in the Central Willamette Valley. PhD thesis. Oregon State

University, Corvallis. 71 pp.

© 2007 Oregon State University. This publication may be photocopied in its entirety for noncommercial purposes.

This publication was produced and distributed in furtherance of the Acts of Congress of May 8 and June 30, 1914. Extension work is a

cooperative program of Oregon State University, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Oregon counties.

Oregon State University Extension Service offers educational programs, activities, and materials without discrimination based on age,

color, disability, gender identity or expression, marital status, national origin, race, religion, sex, sexual orientation, or veteran’s status.

Oregon State University Extension Service is an Equal Opportunity Employer.

Published December 2007.

Filbertworm and filbert weevil

Filbert aphid and hazelnut aphid

Conclusions

For more information