SWEETPOTATO PRODUCTION

IN CALIFORNIA

C. SCOTT STODDARD, UC Cooperative Extension farm advisor,

Merced and Madera Counties; R. MICHAEL DAVIS, UCCE plant

pathology specialist, UC Davis; and MARITA CANTWELL,

UCCE postharvest specialist, UC Davis.

PRODUCTION AREAS AND SEASONS

In 2011, California sweetpotato (Ipomea batatas) produc-

tion for processing and fresh market consumption was

estimated to be a $130-million industry, with production

of about 582 million pounds on 18,200 acres. In an aver-

age year, California produces 20% of the sweetpotatoes

grown in the United States and is the second-largest-

producing state, behind North Carolina. While sweetpo-

tatoes are usually regarded as a Southern crop, California

production exceeds that of Louisiana and Mississippi

combined. Merced County accounts for approximately

90% of the commercial acreage planted to sweetpotatoes

in California, but they can be grown in many of the warm

agriculture production areas of the state.

The primary production area for sweetpotatoes is in

sandy soils between Atwater and Turlock in Stanislaus

and Merced Counties, centered on the Highway 99 cor-

ridor in the center of California. Additional commercial

production occurs in Kern County. Typical highly pro-

ductive soils are sandy to loamy sand in texture. Yield

and quality are poorer in heavy soils.

Hotbeds for producing transplants are typically

installed from the first week of February through early

March. Transplanting from the hotbeds begins in late

April and continues into June, though transplanting

for seed fields may occur as late as July. Commercial

harvest from early plantings begins in mid-July, but

crop yields are low at that point so the amount of the

harvest is limited. Regardless of location, the bulk of

the harvest occurs in September and October, when the

roots are dug out and placed into storage. Harvest usu-

ally is complete by early November.

CLIMATE

Sweetpotatoes are a warm-season, frost-sensitive

crop. Daily maximum air temperatures between 85°

and 95°F (29.7° and 35.3°C) are ideal for root produc-

tion, but temperatures above 100°F (>38°C) are not

harmful so long as the crop is adequately irrigated

and temperatures drop at night. Recent growth cham-

ber research has shown that high day/night tem-

peratures (95°/80°F [35°/27°C]) result in decreased

storage root production, but in production areas of

California elevated temperatures like this rarely occur

at night. Because they are sensitive to even a light

frost, sweetpotatoes are planted in spring after any

chance of frost has passed. For the same reason, the

crop must be harvested before the autumn onset of

heavy frost and cold rains, since the roots may sustain

chilling injury if they are subjected to temperatures

below 50°F (10°C) for even a few hours.

VARIETIES, PLANTING TECHNIQUES,

AND SOILS

The edible sweetpotato is an enlarged storage root that

grows in various shapes, sizes, and colors. Varieties,

particularly those grown for market use, fall into four

categories based on their skin color and flesh char-

acteristics: red skin with orange flesh (so-called “red

yams”), copper-rose skin with orange flesh (“yams”),

cream-tan skin with yellow flesh (“sweets”), and

burgundy-purple skin with white flesh (“Oriental”).

Most packers have a supply of all four types, though

some will specialize in certain types more than others.

Orange-flesh sweetpotatoes have a moist texture after

baking, whereas sweets may not.

Diane is the main cultivar for the red-yam cat-

egory. It is characterized by dark red, smooth skin

with deep orange flesh. These qualities make it the

premium yam-type sweetpotato. At the retail level,

it is often labeled incorrectly as Garnet, which was

the red-skinned variety that established this mar-

ket class in the 1970s. Diane is marketed mainly in

California, where red-skinned sweetpotatoes are

University of California

Agriculture and Natural Resources

http://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu • Publication 7237

Vegetable Production Series

VRIC.UCDAVIS.EDU

UC Vegetable Research

& Information Center

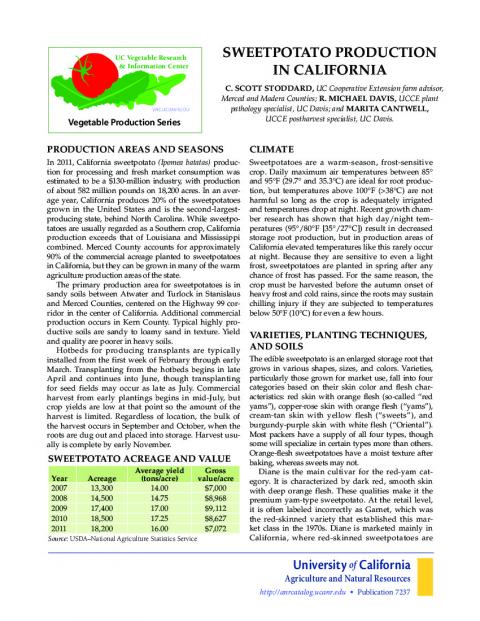

SWEETPOTATO ACREAGE AND VALUE

Year Acreage

Average yield

(tons/acre)

Gross

value/acre

2007 13,300 14.00 $7,000

2008 14,500 14.75 $8,968

2009 17,400 17.00 $9,112

2010 18,500 17.25 $8,627

2011 18,200 16.00 $7,072

Source: USDA–National Agriculture Statistics Service

http://anrcatalog.ucanr.edu

vric.ucdavis.edu

2 • Sweetpotato Production in California • ANR 7237

popular and often command a higher price. The

yam types Beauregard and Covington have copper-

colored skin with deep orange flesh. For 20 years,

Beauregard was the most commonly grown variety

in California and the United States, but in 2009 it

was displaced by Covington. Beauregard, while sus-

ceptible to nematode damage, has yield and storage

characteristics that are superior to those of Covington,

but Covington is adaptable to a wider range of grow-

ing environments and has better resistance to diseases

and nematodes.

Golden Sweet and O’Henry are major varieties in

the sweets category. They are characterized by their

cream-colored outer skin and yellow interior flesh.

Dry matter content for Golden Sweet is typically 30 to

35%. O’Henry has recently displaced Golden Sweet in

both acreage and production. O’Henry is actually an

off-type Beauregard that naturally mutated to have

white skin and yellow flesh. It contains about 20 to

22% dry matter and does not have the dry-flesh flavor

and texture profile of Golden Sweet.

Oriental types, and most commonly Japanese

yams, make up an important and growing part of the

California sweetpotato industry. These include a vari-

ety of flesh and skin colors, including white, purple,

and red, but their flesh is typically dryer than that of a

Beauregard, with a more subtle flavor. The most com-

mon varieties are Kotobuki and Murasaki-29, both of

which have burgundy skin and white, dry flesh.

Recently released sweetpotato cultivars have been

granted patent protection, and growers are legally

restricted in the sale and distribution of these roots

for propagation. Both Covington (released from

the North Carolina State University Agriculture

Experiment Station) and Murasaki-29 (from

Louisiana State University Agriculture Experimental

Station) are patented. Future releases of new variet-

ies, like the sweet variety Bonita released in 2012,

will carry similar restrictions. Proceeds from the sale

of plants and roots from these varieties support the

breeding programs that developed them.

Sweetpotatoes are vegetatively propagated from

plant cuttings, called “slips,” from hotbeds. “Hotbed”

is the name used for the nursery area where sweetpo-

tato roots saved from the previous year are used to

produce new plants for the production fields. These

“seed roots” for the hotbeds typically are placed on

the ground in February and covered with a shal-

low layer of soil. Medium-sized potatoes are typi-

cally used for this purpose, but any size root can

be used to produce sprouts. Commercial hotbeds

in California are typically 8 feet (245 cm) wide and

may be several hundred feet long. For warmth, clear

plastic is stretched over iron rods bent into half hoops

over the bed to form an elevated plastic tunnel run-

ning the entire length of the bed. Hotbeds are so

named because they are warmed by the decomposi-

tion of cotton gin trash that is buried under the roots.

Cold beds, which do not use gin trash, are also used

for propagation. It takes approximately 500 to 800

pounds (225 to 365 kg) of roots, depending on the

variety, to furnish cuttings for a 1-acre (0.4-ha) plant-

ing of the crop.

Sprinklers are used to irrigate hotbeds until the

plants are ready to be transplanted—when they are

about 12 inches (30 cm) tall. The plants are then cut

at or slightly below the surface of the soil. Cuttings

from the hotbeds are mechanically transplanted in

two rows on 80-inch (200-cm) prepared beds from

mid-April through the end of June. Most fields are

drip irrigated, but some are furrow irrigated. Cuttings

are watered heavily at transplanting and then surface-

applied drip tape is set on top of the beds between the

two rows. Cuttings are planted 9 to 15 inches (23 to 38

cm) apart within the row. Typical plant populations

are 13,000 to 17,000 plants per acre.

Soils selected for sweetpotato production gener-

ally range from sand to loamy sand in texture, are

well drained, and are low in salts. While the plants

can grow in heavy soils, root yield and quality will

be reduced. Acidic soil conditions (pH 5.5 to 6.5) are

preferred, as this helps suppress pox, a root disease.

Sweetpotatoes are moderately sensitive to soil salts: a

10% reduction in yield can be expected if soil electri-

cal conductivity (EC) exceeds 2 dS/m. Furthermore,

roots grown in salty soils do not store well and are

more likely to develop the abiotic disorder “tip rot”

after a few months in storage.

IRRIGATION

More than 95% of sweetpotato fields use drip irriga-

tion; the remaining acreage uses furrow irrigation.

Unlike many transplanted crops, no sprinklers are

used to establish the crop, nor are the fields typically

pre-irrigated. Producers rely on copious amounts of

transplant water (> 2,000 gallons per acre [> 19,000

L/ha]) and the expeditious installation of drip sys-

tem lines to keep water stress at a minimum for the

newly planted crop. Maintaining adequate moisture

in the soil immediately surrounding the plants for the

first 17 days after transplanting is critical to promot-

ing the initiation and development of storage root

cells. Surface drip is used because of root intrusion

problems in buried lines. A typical installation has

one drip line running down the center of an 80-inch

bed, irrigating two rows of plants. Occasionally the

drip line will be moved from the center of the bed

and placed directly in the plant row to facilitate early

root growth, but this is generally avoided because it

stimulates weed germination in the plant row.

Irrigation frequency depends on the crop’s evapo-

transpiration (ET) requirements and the water-

3 • Sweetpotato Production in California • ANR 7237

holding capacity of the soil, but may be done daily

once the plants are fully established. Total water

use typically ranges from 2.5 to 3.5 acre-feet per

acre. Irrigation cut-off dates vary depending on

crop development and harvest schedule. Irrigation

should be halted when jumbo-sized roots exceed

33% of total root production, unless the crop is slat-

ed for processing and maximum total tonnage is

desired. There is no evidence to support the practice

of discontinuing drip irrigation 2 to 4 weeks prior to

harvest in order to toughen the skin and minimize

harvest losses, but such practices do reduce the

development of scurf if the roots have already begun

to develop this disease (see Pest Management,

below).

FERTILIZATION

Sweetpotatoes have an extensive root system and

make efficient use of soil nutrients. The vines and

leaves respond better to applied fertilizers than do

the roots. On average, the crop removes 2.7, 1.0, and

4.5 pounds of nitrogen (N), phosphate (P2O5), and

potash (K2O) per 1,000 pounds of harvested roots.

Phosphorus (P), potassium (K), zinc (Zn), and boron

(B) fertilizers should be applied preplant or immedi-

ately after transplanting, as determined by soil tests.

Up to one-half of the crop’s N requirements can also

be applied at this time, with the remainder applied

later through the drip tape to match the growth char-

acteristics of the field. Because the cuttings used for

transplants are rootless, they are very sensitive to fer-

tilizer burn, so inclusion of fertilizers in the transplant

water is not recommended.

High-yielding, drip-irrigated fields require N

rates of 125 to 175 pounds per acre (140 to 200 kg/

ha), one-half of which is applied through the drip

tape during the first half of the season when the

plants are rapidly growing. If P is needed, 50 to 100

pounds of P2O5 per acre (56 to 112 kg/ha) is applied

before planting. Potassium (K) is readily taken up by

the leaves and roots of the crop, but has been shown

to have only modest impacts on sweetpotato root

yield. If required, 200 to 250 pounds of K2O per acre

(225 to 280 kg/ha) should be applied to replace what

was removed at the previous harvest. Unlike phos-

phorus, potassium is sometimes applied through the

drip tape. Preplant fertilizer should be placed in a

band 9 inches to the side of the plant row at a depth

of 8 to 10 inches. Alternatively, a banded applica-

tion of potash directly beneath the drip tape in the

middle of the bed can be used. This latter method

relies on irrigation water to move the potassium to

the plant.

INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT

Hotbeds are a distinct and separate part of the whole

production system for sweetpotatoes, and as such

they require different pest management techniques

than are used for the production fields. The prima-

ry method of pest control for the past two decades

has been preplant soil fumigation with methyl bro-

mide plus chloropicrin, followed by hand weeding

as needed. This fumigation regimen provides nearly

100% control of weeds, nematodes, and fungal dis-

eases. However, with the implementation of laws that

require the phase-out of all but the most critical uses

of methyl bromide, alternative management tech-

niques are needed. These include 1,3-D (Telone) plus

chloropicrin (Pic) applied under plastic tarp, metam

sodium/metam potassium, preplant fungicides and

herbicides, and solarization.

Weeds are the main pest problem in sweetpota-

to hotbeds, and hand weeding remains an impor-

tant component of hotbed weed management.

Nonselective foliar herbicides (glyphosate, pelargonic

acid) are occasionally used postemergence on weeds,

but before the crop plants’ emergence. Annual grasses

can be effectively controlled with postemergence grass

herbicides such as fluazifop (Fusilade), sethyoxydim

(Poast), and clethodim (Select). Other occasional pests

include aphids, which may need to be controlled in

order to limit their impact on the growth of plant cut-

tings. Fungicides are available to help control fungal

diseases, but in general these can be managed more

effectively with good seed selection and irrigation

management. If fungicides are used, applications are

made to the seed roots prior to their being covered

with soil. Both thiabedazole (Mertect) and dichloro

nitroanaline (Botran) can help reduce the incidence of

scurf development on seed roots in the hotbed.

Weed management. The primary method for weed

control in sweetpotato production fields is mechan-

ical cultivation, supplemented by hand weeding.

Hand weeding, though heavily used, is not the pre-

ferred method due to the expense and the amount of

time it requires. Because sweetpotatoes are a small-

acreage specialty crop, only a limited number of

effective chemical control options are available for use

in the United States, and preplant herbicides are not

commonly used in California. Perennial and annual

grasses can be controlled with postemergence grass

herbicides such as fluaziflop (Fusilade), sethyoxydim

(Poast), and clethodim (Select). A crop oil concentrate

is often required to maximize effectiveness. Annual

and perennial grasses should be of the proper size

and actively growing for good control. Consult your

farm advisor or PCA for details and follow label

directions with regard to chemical use restrictions.

4 • Sweetpotato Production in California • ANR 7237

Since the main method of irrigation is through

drip tape set on top of the bed, the bulk of weed

germination occurs in this wetted zone, so mechani-

cal cultivation down the center of the bed (with the

drip tape temporarily moved aside) is an effective

way to control many weeds, provided that the cul-

tivation is done when the weeds are still small and

before the crop begins to vine, typically around 5

to 6 weeks after transplanting. Directed sprays of

glyphosate (Roundup) with shielded sprayers can

also provide effective control of most weeds down the

drip line, and eliminates the need to move the drip

tape. Chemical contact with the crop foliage should be

minimized in order to avoid damage to desirable root

development.

Disease identification and management.

Sweetpotatoes are vegetatively propagated: roots are

sprouted and those sprouts are transplanted to the

field to produce more roots. True seed is not used in

commercial production because sweetpotatoes rarely

flower. An unfortunate consequence of not using true

seed, however, is that viruses and many soilborne dis-

eases can accumulate in the plants, greatly diminish-

ing both yield and quality. Common diseases include

russet crack (caused by the russet crack strain of

sweetpotato feathery mottle virus [SPFMV]), soil rot

(pox, Streptomyces ipomea), charcoal rot (Macrophomina

phaseoli), scurf (Monilochaetes infuscans), stem rot

(Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Batatas, race 1), and vari-

ous forms of soft rot (multiple causal organisms,

including Erwinia, Pythium, Rhizoctonia, and Fusarium

spp.). The fungal diseases are best controlled by using

disease-free seed (roots) and by cutting transplants

above the ground. Fungicide dips can offer addi-

tional protection from stem rot, but because recently

released varieties have been bred to be resistant to this

disease, this practice becomes less and less common

every year. Soil pox is controlled with field fumiga-

tion and through the use of resistant varieties; manag-

ing soil pH and avoiding late season plant dates can

also lessen the severity of this disease. Crop rotation

is an important component of disease management in

sweetpotatoes; a given field should not be planted to

sweetpotatoes for more than three years in succession.

Once planted in the field, sweetpotatoes imme-

diately start to acquire viruses. Research has shown

100% infection by the end of the first season, albeit at

low levels within each plant. As these roots are saved

year after year, virus levels build up and yield and

root quality decline. The only effective way to control

virus diseases is through the use of virus-tested plants

or roots. The process, developed by UC Davis in the

1960s, involves aseptically cutting the meristem (usu-

ally 0.5 mm long) from the very tip of a sprouted root.

The cut meristem is placed in a test tube and grown

on synthetic nutrient agar to produce a new plant,

which is then transplanted in the greenhouse and

grown out for virus testing. The whole process takes 6

months or longer, depending on the sweetpotato vari-

ety. Once verified as virus-free, the new plant is prop-

agated through cuttings, which are sold to growers.

Insect and pest management. The main insect

pests impacting sweetpotatoes are wireworms

(Limonius spp.) and grubs (various species, but most

likely the larvae of scarab beetles such as the ten-lined

June beetle [Polyphylla decemlineata and P. sobrina]).

Preplant soil fumigation with products that contain

1,3-D or metam sodium is the most effective way to

control these pests. Preplant insecticides offer some

pest suppression, but their degree of efficacy is more

variable. Nonetheless, preplant insecticides are used

in areas where no fumigation is allowed, such as

in buffer zones. Occasionally, western yellowstripe

armyworm (Spodoptera praefica) can become a prob-

lem that will need to be controlled. Sweetpotatoes

have a very high threshold for leaf damage before

yields are affected, but control measures are generally

warranted when the loss of leaf canopy exceeds 30%.

Several good insecticides are registered for this use;

consult your farm advisor or PCA for detai